During a seminar on the subject of empowerment, one of the participants asked me whether managers did not also have a duty of care towards their employees. To stimulate discussion, I told the group the story of the Pullman strike. Until the big strike of May 1894, which spread across the nation from the Pullman factories south of Chicago, George Pullman had been considered a benevolent entrepreneur. He was a welfare capitalist who built over 12,000 comfortable homes and houses with sanitary facilities and gas connections for his workers, while many other American workers had to live in the shabbiest housing imaginable. There were schools for their children, he had a theatre and a church built and a park planted for them.

Up to the time of the recession, when he imposed wage cuts, his workers' incomes were also significantly higher than those in comparable companies. In particular the many immigrants from Europe, who often found work with Pullman after having gone through several stations in which they had to fight for their lives and those of their families under appalling social and hygienic conditions, saw Pullman as a material and emotional protector and appreciated the well-ordered life in his city. The fact that such a strike originated in this very city seems at first to be an irony of fate.

In his excellent book on authority the American sociologist Richard Sennett also describes the flip side that this welfare capitalism had for the workers. They were completely dependent on George Mortimer Pullman, who saw himself as the father of a large family. They were not allowed to own the houses in which they lived themselves. They were in a state of unpropertied bondage, a fact of which they became all the more aware the less they had to fight for their daily survival. The loss of a worker's job also meant the loss of his home, the children had to change schools and the entire family lost its social contacts. In addition, due to his paternalism, Pullman was seen by the workers as being personally responsible for every mistake his managers made, for every fluctuation in demand that made layoffs necessary, for simply everything that happened in his company.

Pullman ran his company in a paternalistic-authoritarian and benevolent manner. When they started working for him, this was obviously helpful for many workers as it offered them the security they desperately needed after times in which they had suffered acute fear for their very lives. Over time, however, their needs changed. But since Pullman continued to behave as he did, they saw themselves severely restricted in their development, their need for property, freedom, and responsibility for their own lives.

An early 20th century social reformer, Jane Addams, compared Pullman to Shakespeare's King Lear. Lear wanted to pass his kingdom on to his three daughters and demanded declarations of love in return for this material gift. When his favourite daughter rebels against this request, he becomes furious and blind with rage and outcasts her. He sees it as his paternal and/or royal right to tell others what they should think and how they should act.

The manager Pullman behaved like Lear. As long as his workers, like Lear's daughters, accept both his benevolence and the associated control gratefully and unconditionally, the system works. To quote the title of a novel by Heinrich Böll, in which he described the social effects of excessive control:

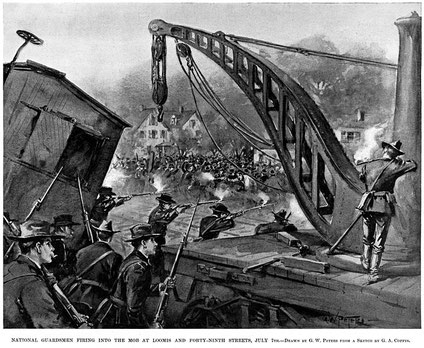

“The Safety Net", too, is a net that imprisons. But there will be resistance against a net. As soon as Lear's daughter and Pullman's workers become independent and want to make their own decisions, the "fathers" are hopelessly overwhelmed by the situation and react with completely inappropriate violence. They cast out their daughter or violently suppress the strikes and dismiss their workers. They justify their behaviour by the fact that they do much more for those they regard as subordinates than is strictly necessary. Lear is ready to hand over his kingdom to his daughters ahead of time, Pullman builds comfortable houses for his workers. However, empowerment does not require one-sided benevolence, but mutual fairness on an equal footing and the awareness that leadership has a limited playing field.